The Three Axes of Economics

Economic discourse is not so simple anymore. Here's my attempt to explain the current trends

The terms ‘Left-wing’ and ‘Right-wing’ are political terms. Economists need a better vocabulary. ‘Left’ and ‘Right’ do not accurately describe perceptions of the role of the state, or attitudes to globalisation. As the neoliberal economic consensus shifts, it is crucial to understand which aspects of economic policy are being challenged, and which are not. This post represents my attempt at conceptualising this change.

I identify three key struggles: the clash between economic equality and competition, the clash between state intervention and laissez-faire economics, and the clash between globalisation and economic nationalism. I then explain the realignment currently taking place within the field, and the re-emergence of an old economic school of thought.

I’ll preface this post by stating I am not endorsing any particular element of these axes. The ideas I present draw heavily from the Political Triangle, created by Curt Doolittle. This post focuses solely on economics, and is not intended to reflect social political positions. I’m merely attempting to explain what I see happening in the world of economics.

Without further ado, I present The Economic Triangle:

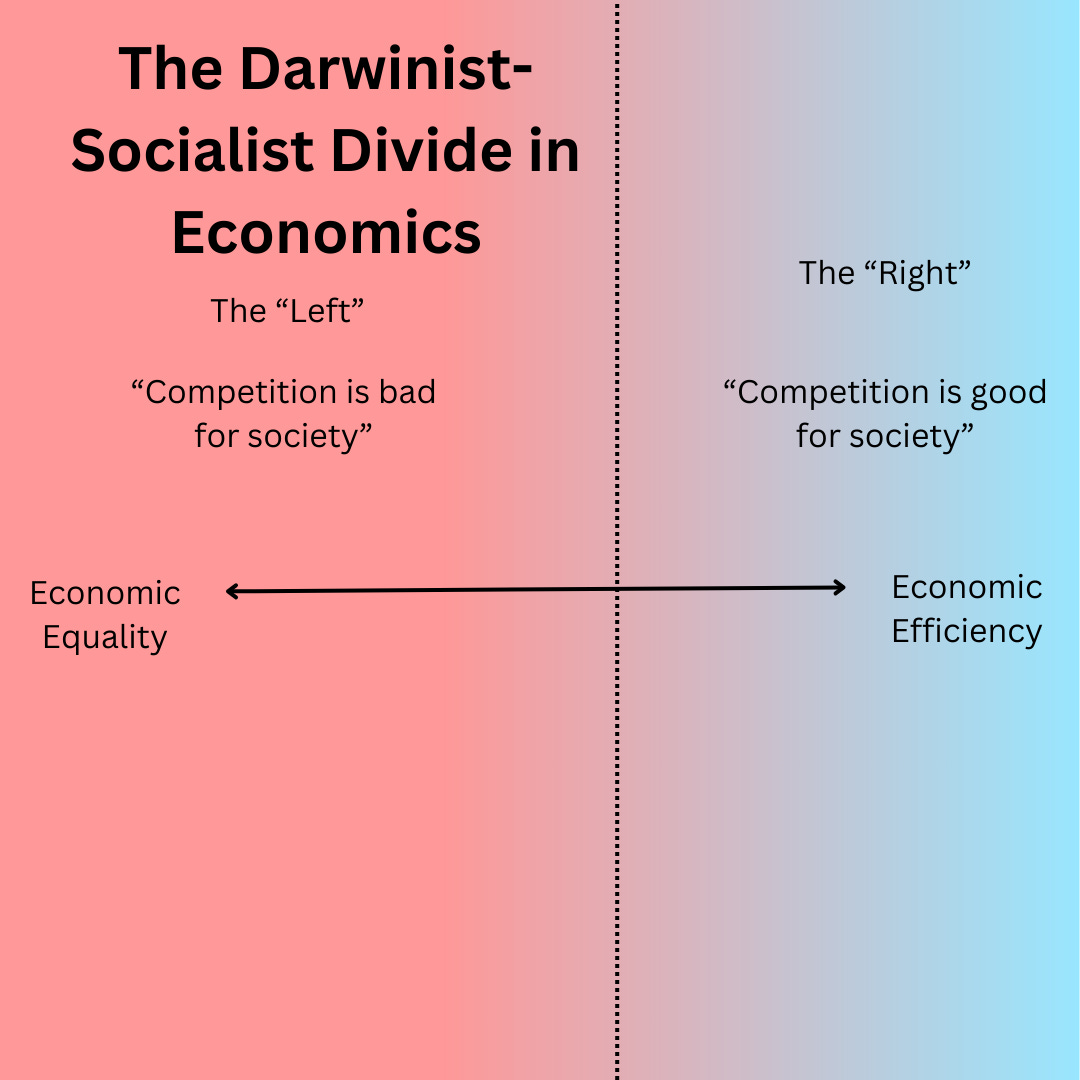

The Fairness Axis: Equality and Competition

In the 1980s, the world saw a clash of two economic ideas: free market capitalism, and centrally planned command economies. Communist governments believed in state control of the economy, in order to bring about equality. Capitalist economies, on the other hand, believed in private property, non-interventionism and free markets. These ideas were led by politicians on the political right, and so ‘right-wing’ or ‘conservative’ began to be associated with these ideas. As Communism collapsed, the capitalist viewpoint seemed vindicated.

Although the Cold War is over, its language is often used, where ‘right-wing’ can refer to either fascism or libertarianism. The core idea, however, that unites those seen as ‘right’, is that society has winners and losers, and that competition is good for society. Competition creates winners and losers, but through the process of competition, progress occurs. In economics, this is often characterised through ‘creative destruction’, the means by which some industries and companies fail and are replaced by others. This often occurs through the marketplace, however, the core of this axis is competition.

Hence, I called the extreme of this axis ‘Darwinism’. It follows that societal progress is best served by the survival of the fittest. The rewards of the society go to the winners, whereas those who lose are forgotten. Competition is the idea that most unites factions on the “Right” economically, whether that be competition between individuals, firms or nation-states.

On the other side of this axis lies Socialism. Whilst most command economies no longer exist, their motivating factor still does: equality. In this chart, socialism is opposed to competition - it seeks to raise up the ‘losers’ of society and reduce inequality by restricting the gains of the ‘winners’. It is heavily associated with compassion towards the unfortunate, and manifests most in economics through welfare and progressive taxation.

This axis can best be termed the ‘fairness’ axis. In general, those who align with the Darwinist side believe that it is fair that the rewards of the society go to those out-compete the rest. It is comfortable with inequality, believing it necessary to motivate competition. Those on the Socialist side believe it is unfair that some in society will be much better off than others. Inequality, for a Socialist, is unfair. Competition, rather than being good for society, is destabilising, and its excesses should be limited, often through state intervention.

Since the early 1900s, the welfare state has been a staple of most countries, and so this axis tends to be less polarised economically. There are very few economists arguing completely against any form of pursuit of equality, as well as very few advocating pursuit of perfect equality with no competition. The debate in this axis is typically what level of inequality is a society willing to accept in order to both incentivise progress and assist those who, often through no fault of their own, cannot compete.

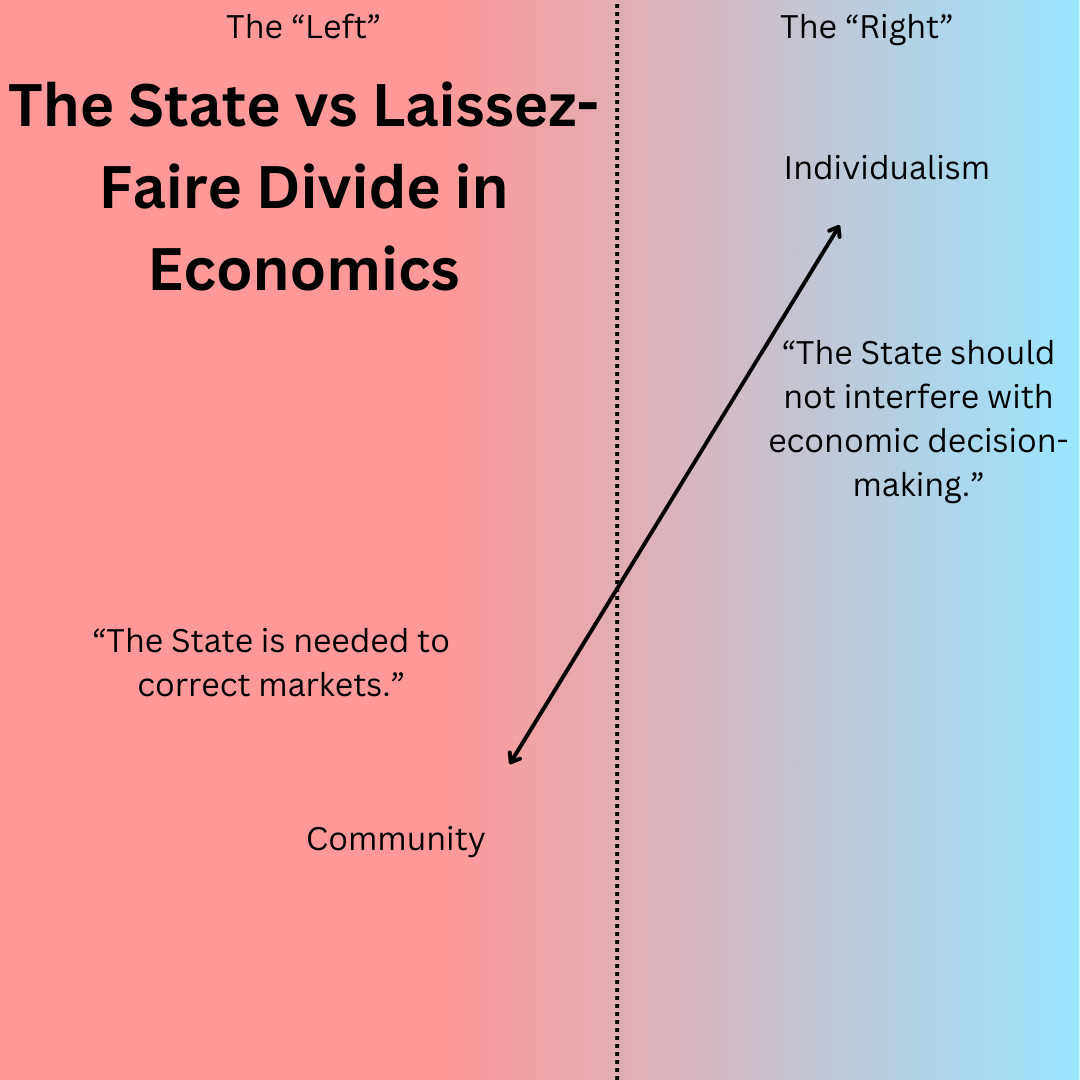

The Government Axis: Laissez-faire vs State Intervention

In the West, particularly the United States, the left-right divide was typically about the role of the state. However, unlike the fairness axis, it is not as clearly delineated into ‘Left’ and ‘Right’. Many who pursue equality do not wish for strong state intervention, and many see the need for state intervention in the economy for areas other than equality. However, broadly, state intervention is more seen as a left-wing economic concept.

In economics, state intervention is often seen as the solution to correct ‘market failure’. That is, when the outcome of markets is not socially desirable for society. This is usually done for the common good, however, a corrupt state can often said to be acting in reverse.

The role of state intervention has been in discussion within economics since the days of Adam Smith. Classical economics espouses the virtues of the ‘Invisible Hand’ of the market. It claims that the government could never know enough as the collective intelligence of millions of individual decision makers, buying and selling, whose interactions form markets. The phrase ‘laissez-faire’ (French for ‘do-nothing’) describes the extreme view of the state’s role in an economy. It prioritises individual decision making, and seeks not to infringe on those rights whenever possible.

The collapse of the Communism was seen to vindicate laissez-faire economic policies. However, during periods of recession, economic downturns are often seen as reasons for a state to involve itself to address problems caused by markets, especially after the 2008 Financial Crisis, and the subsequent government interventions.

The International Axis: Globalisation vs Economic Nationalism

This axis is the most recent, and one that economists have not had to engage with for many years. Since the end of World War Two and the beginning of the ‘Bretton Woods’ era, globalisation has seemed like an unstoppable force. However, since around 2016, trends towards increasing economic integration have slowed down, and in many cases reversed.

Prior to 2016, free trade and openness was widely seen as beneficial. Protectionism was seen as a relic of the Great Depression era. The benefits of globalisation were shown by rapidly decreasing global poverty, falls in prices of almost all goods, with consumers around the world benefitted with a much wider array of goods.

However, the clash between globalisation and economic nationalism is not a new one. Free trade only began to take off in the second half of the 19th Century, and was reversed during World War One. In the 20th Century, especially the Asian Tigers, focussed on ‘export-led’ growth. The influx of labour competition from trade sparked a backlash against globalisation in developed nations, and a return to seeing international trade as a threat to national sovereignty. Economic protectionism has begun to emerge on both the political right and left in order to compete more effectively with foreign competitors. Whilst free trade tends to view other countries as co-operators to increase overall global wealth, the zero-sum economic point of view sees international trade as a threat to economic security and a field of competition between countries.

This axis is one that least aligns with typical left-right. Those who seek to protect exporting industries may do so for nationalistic reasons, or they may do it to protect the livelihood of poorer workers in society. Economic Nationalism comes at the intersection of both state intervention and Darwinism. Instead of its focus on competition between companies and workers, it sees international economics as a competition between nations.

Economic Nationalism often seeks to limit its exposure to the rest of the world, either through a pursuit of autarky (self-sufficiency) or mercantilism (maximising the difference between exports and imports). Mercantilism has a more negative view of imports than exports, seeing other countries as markets to sell to, but not buy from. Autarky is a complete rejection of trade in either direction from other countries, and is very rarely seen today.

Combining the Axes

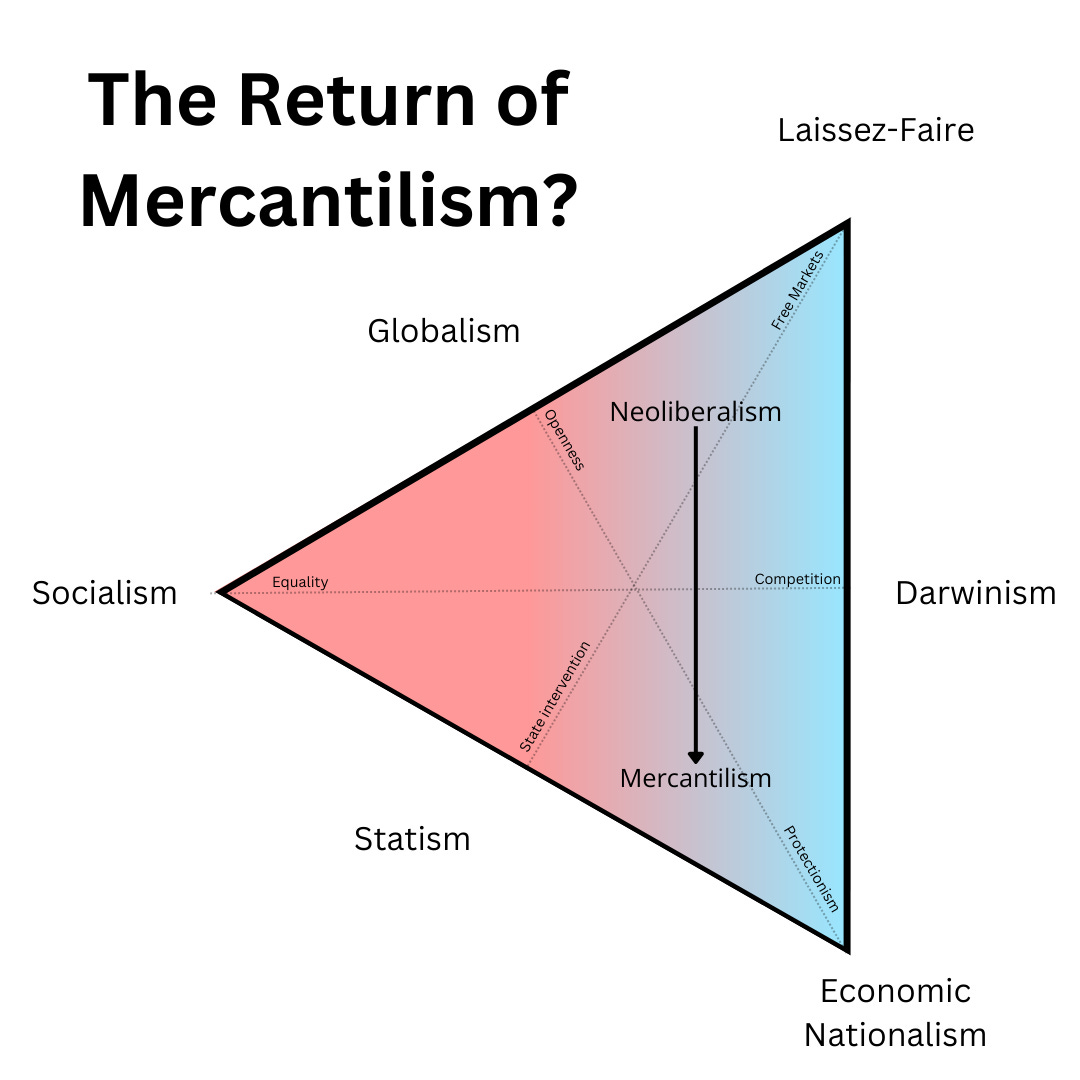

When combining the axes, I tended to focus on the positive elements of each extreme. Whilst most societies are combinations of different economic philosophies, the different positions of often founded in sincerely-held beliefs around the fairness, the government and the nation.

For the triangle itself, I drop the left/right dividing line, however, the ‘left-right’ dichotomy can simply be viewed as the equality vs competition axis.

The points of the triangle show the more extreme positions. Extreme laissez-faire is the opposite of socialism, statism and economic nationalism. Socialism rejects laissez-faire, market Darwinism and economic nationalism, whilst economic nationalism rejects laissez-faire, globalism and socialism.

The link that is perhaps the most unusual is the positioning of globalism in between Socialism and Laissez-Faire. The ‘International Axis’ in its extreme highlights the value of openness to cosmopolitanism and to the world, hence is compatible either with complete free markets or the pursuit of equality.

The same applies principle is applied to the other two:

Both Economic Nationalism and Socialism in their extremes require state intervention.

Both Laissez-Faire and Economic Nationalism put competition above equality.

Where are we now?

I initially planned to write this article about the increasingly popularity of mercantilism and protectionism with respect to globalism. Many governments are espousing economic policies around protectionism. However, it didn’t see apparent that this was a right-wing or left-wing movement - it was both. Competition still remains, however, nation-states are beginning to be seen as the units of change, with the rise of industrial policies from both left and right-wing governments.

In the political triangle, there are two ways that mercantilism manifests. The first the move away from openness and towards security. Nations are beginning to feel other countries represent risks rather than opportunities. Secondly, this represents a move towards state intervention and away from laissez-faire economics. The overall move is one downwards on the triangle, towards nationalism and statism, and away from laissez-faire and free trade.

This move away from economic integration and towards nation-state competition was a surprise for many economists. The benefits of trade and globalisation seemed, to many classical economists, obvious.

However, throughout history, moves towards statism and economic nationalism have accompanied shifts between eras of peace and cooperation and eras of conflict and competition. Globalisation has taken place under the ‘Pax Britannica’, a period of relative peace between 1815 and 1914, and the ‘Pax Americana’, the period from 1945 to the present. Mercantilism economic policies were popular before 1815, especially during the Napoleonic Wars, and many protective economic policies came in around the period of 1914 to 1945 across the world.

Summing up

This way of conceptualising the different trends in economics is not supposed to be holistic. There are other dimensions of economic policies that do not fit neatly into this triangle, however, I hope you consider it a useful framework to understand the different economic schools of thought. It might be that a triangle is not the best shape - three dimensions would like provide a more complete picture.

Like I mentioned at this beginning, this is an attempt for me to explain economics, not prescribe policy. The Economic Triangle is a descriptive tool, and one that I hope is useful for others. If you have any feedback or disagreements, I welcome comments below.

For this post, I was inspired by the Political Triangle, from which I borrowed many concepts. In future posts, I aim to dive more into mercantilism and economic conflict, taking examples from historical clashes to see what lessons we can learn for today.

This is pretty good overall! I think the political trichotomy is genius and I've even made my own charts/versions of it which you can see on my Xitter: https://x.com/jonah_da_mann/media

(I'm not a fan of Curt Doolittle though. I am strongly opposed to neo-feudalism and I think his beliefs about Jewish people are very disturbing.)

I do have one critique of the economic triangle you've created above, however. And I mean it in a constructive way.

I think the Globalism/Protectionism (Openness/Economic Nationalism) spectrum is misplaced. Right now, it is positioned in such a way that it makes Economic Nationalism/Protectionism look like it is exclusively the domain of Far-Right Authoritarianism (e.g., Fascists, Czarists, absolute theocracies, feudal monarchies, Franco's autarky, etc.).

However, it isn't. Economic Protectionism was also evident in Mao's China, Stalin's Russia, Pinochet's Chile, and many other Collectivist/Statist societies as well - they deliberately closed themselves off because they didn't want to be exploited internationally by capitalist countries. The current Trump administration in the U.S. appears to be doing the same thing as well (I recommend checking out Noahpinion's substack - he has written several posts which all do a great job explaining this).

I think the Globalism vs Protectionism (Openness vs. Economic Nationalism) spectrum is really just another version of the Statism/State Intervention vs Laissez-Faire/Free Markets spectrum.

So that being the case, what should take its place?

Honestly, I think a fitting replacement would be a Service Economy vs. Feudalism. In the former, everyone has equal rights and opportunities (e.g., is entitled to the same economic services). Whereas in Feudalism, only the higher-ranking individuals (e.g., the nobility and higher castes) get to enjoy such services--the lower classes remain locked out; in a state of servitude.

In other words: I think the spectrum should range from: EVERYONE gets to live like a King (for a price), to: only ONE person (or a small group of people) get to live like Kings.

Here's my take on how Economic systems map to the political triangle: https://x.com/jonah_da_mann/status/1911815519688106220

And here's another thing I've noticed about it, regarding Democracy vs. Totalitarianism: https://x.com/jonah_da_mann/status/1911964739346854279

Thanks for this interesting read. I’m wondering if globalism-nationalism is really an independent axis of Economics. I think if you take a narrow Economics approach, this is just another version of free markets vs state control. No real laissez-faire libertarian can ever be an economic nationalist (I appreciate that in practice many will reconcile those two things by pointing to level playing field issues etc.). Free trade is in theory just an extension of laissez-faire to global markets. The polarity of the two of course does arise the moment you include other considerations, of which there have been many from both right and left (from “maintain our jobs” to outright xenophobia in its various forms).